Craftspeople of 3,500-year-old jewellery can be traced through the traces they left.

This edition of the Ancient Metals newsletter aims to present some background to my approach on ancient metalwork. By examining Bronze Age artefacts, the trained eye can reveal whether the craftsperson used the right or left hand while crafting and in which relation the master and apprentice worked together. This could be demonstrated during my PhD studies a few years ago and the results can be read in the book “Bronze Age Metalwork” published by Archaeopress and open accessible for everyone.

It’s not exactly like getting the cell phone number of Bronze Age craftspeople, but it’s close.

Traces left of the crafting process on 3500-year-old bronze objects can be used to identify the craftsperson, his/her network and unique technical inventions! These traces witness the making of the artefact and are unique to each craftsperson. The study of bronze jewellery from Denmark and Northern Germany revealed some spectacular results. Among other things, it was shown that Bronze Age finesmiths used unique tools such as their nails and individually made spiral stamps to create the rich decoration on the jewellery. A comparison of traces on hundreds of artefacts made it possible to determine workshops and their supply area. Some of these workshops in Danmark were connected through an active exchange of knowledge, likely through people’s active mobility. The connection reached as far as northern Germany, as some tool traces could prove.

It is very likely that the exchange of apprentices was already introduced in the Bronze Age to secure an ongoing development in technological solutions, styles and ideas.

For example, a workshop existed in the north of Zealand during the middle Bronze Age, where many of the largest belt ornaments were made. Objects from this workshop are characterized by a distinct triangular pattern, large, very dense spirals and hourglass impressions with two different ends (see figure). The Langstrup beltplate, which we know from the Danish 200,- Kr. Notes, was made in another workshop on Zealand, a few hundred kilometres to the west. The best way to separate the works of these two large workshops is to look at how the long spike was added to the disc. Both workshops used a highly specialized technique: the decorated flat plate was made first and the spike was cast onto the plate. In the workshop where the Langstrup plate was made, the craftspeople cast the spike from the top, looking at the decorated part of the disc—the northern workshop from the bottom.

“How should we be able to see who made the Langstrup belt plate? “

You need to look at the Bronze Age objects to see manufacturing traces. You need to get familiar with every bit of detail of the piece. Such traces can be errors in the decoration, markers of specific techniques or impressions of special tools. It is sometimes enough to look at the objects with the naked eye. In any case, magnification through a camera lens is sufficient! However, basic metallurgical knowledge is necessary to understand these traces, and an education as a goldsmith helps a lot. Knowing the basic techniques of metalworking makes it possible to associate certain defects with specific techniques. The properties of the metal are the same from 3500 years ago and today. As such, similar tools will leave the same impressions.

For the next step you need imagination. Is the left side of one spiral from the Langstrup belt plate identical and can be fitted perfectly with the right side of the neighbouring spiral, these spirals must be inserted with the same tool. If all spirals are identical and small errors appear in the same place on successive spirals, the tool used must have been a stamp. Thus, the spirals on the Langstrup belt plate are made using a stamp (see figure).

Preserved mistakes in the decoration are the starting point for finding out who made the object. We know some basic behavioural patterns in the way we humans work. These are described in a philosophical and anthropological concept called habitus. Based on this concept, we can define work patterns, typical mistakes, and techniques unique to a craftsperson. Using the same background, we can assign a specific piece of jewellery to one particular region. The society around us, our region-specific worldview and ingrained customs influence us as people in our upbringing and in the way we learn. This concept can answer why we do things the way we do! We have learned to do it in a certain way.

“However, you cannot work metal with fingernails!”

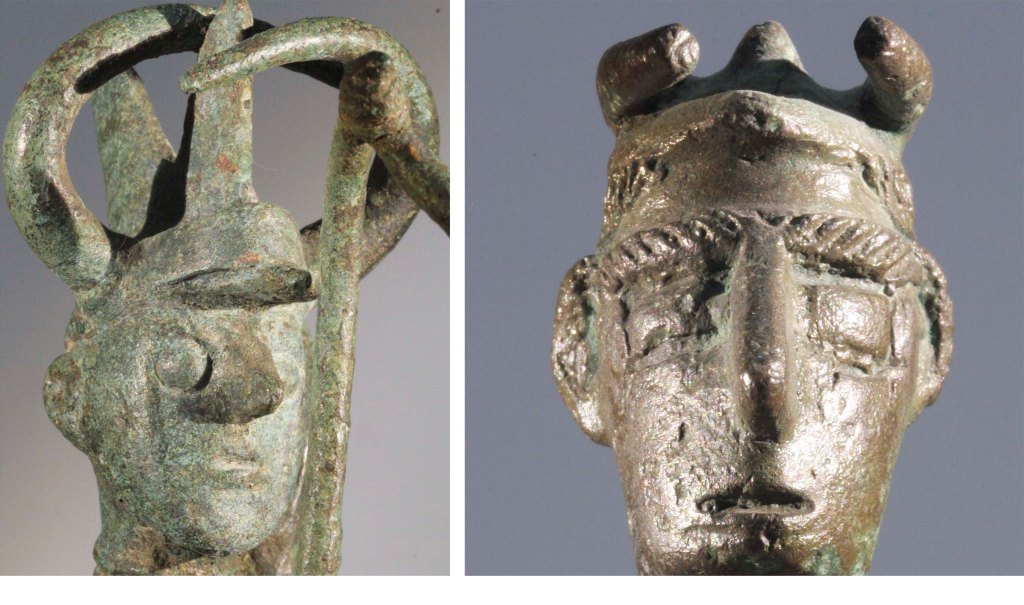

That is absolutely true; bronze is too hard to be worked with tools that are softer than the bronze itself. The detected tool traces, such as nail prints, show that the artefacts were made using the lost-wax method. Bronze Age fine smiths started by melting beeswax and adding fat and minerals to make the wax less sticky. Afterwards, the wax can be shaped as desired and decorated with fingers, wooden tools, and hair. The stamps used for the spirals were most likely modelled from horsehair (see figure). Embedded in fat and twisted, even a few hairs would create a stable shape that could be used multiple times when fitted on a handle. The almost finished model is wrapped in several different clay layers and fired so that the wax melts and leaves a negative of the desired object. Many of the examined ornaments and weapons show that they have been worked a final time after casting with bronze tools.

…

And here the chapter ends for now. For this time there is enough information to be processed. In the next issue of Ancient Metals, we will continue with this topic and explore how crafting traces can illuminate master-apprentice relationships and exchange of craftspeople in the Bronze Age.

Practical Archaeometallurgy 2

In the last issue, I started the chapter series Practical Archaeometallurgy to answer the many questions that may arise when thinking about archaeometallurgy and how archaeometallurgists work. The aim is to present within this chapter some basic techniques and methods used in archaeometallurgy that are necessary to answer archaeological questions.

We learned how to cut a sample. In this case, the cutting of slag samples with a diamond blade saw was illustrated. It might be worth mentioning that some samples need to be treated with much more care, like bronze samples. Here a goldsmith saw is an often-used tool. It is recommended to have some other devices and tools with you when you plan to sample bronze artefacts, such as a leather cloth (to catch the jumping sample), a long rectangular piece of hardwood and a pair of clamps (see figure).

When the sample has the desired size, it needs to be prepared for grinding. Large samples could be ground without a working step in between. Small samples cannot be handled without a proper base. Here, archaeometallurgists use epoxy resins to mount the samples in small round mounting cups. This procedure is called cold mounting and uses, besides the small plastic cups, a two-component resin. The World Wide Web has several guidelines and tutorials that explain step by step the needed procedure to succeed with the mounting (see https://en.archaeometallurgie.de/how-to-sample-mounting/).

However, I would like to add some tips (I myself have been told by my teachers) that will make the procedure more straightforward. Be careful when sorting the small fragments you want to fix in the mould. Remember the labels! All the way through the process have the labels next to the metal pieces and add them to the cast. The mounted samples will appear mirrored in your finished block! Be careful with the epoxy. In Danmark, the handling of epoxy requires specific training and a certificate which indicates how dangerous this material is for your health (wear gloves and goggles). Have enough time! Working with such small samples cannot be done in haste. Finally, you have to allow for more time because the epoxy needs to dry for at least 24 hours.

You see, lab work is fun as you can nearly finish your listening books while mounting samples!